How To Kick: Sound Design Before Mixing

The kick drum can be the pulse that defines the groove. By understanding its anatomy — transient, body, and tail — you can design low end with purpose, whether through samples, synthesis, or a hybrid approach.

How To Kick

In our last post, “What’s a Kick?”, we explored the history and foundational role of the kick drum. Now we move from the why to the how. The goal is to understand the anatomy of a kick so you can better read your samples or design your own from scratch.

Get the sound right at the source. When you design a kick that’s already tailored for its role, any processing you apply later becomes a creative choice, not a corrective one. You’re not fixing problems; you’re adding flavor.

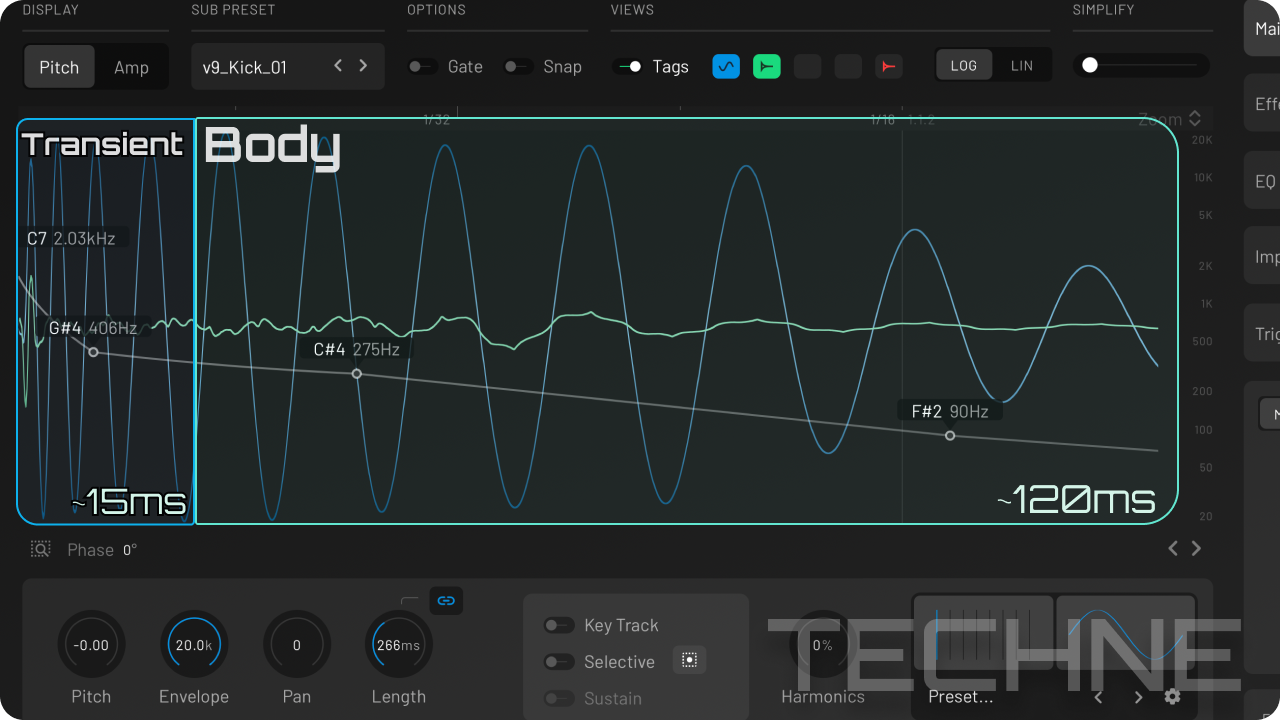

To explore this, we’ll use a kick synthesizer as our main tool, specifically Kick 3. Why? Because it’s a perfect abstraction of the core principles. It gives us a clean, visual way to manipulate the very physics of sound. But these concepts are universal, whether you’re layering samples in a DAW or patching a modular synth. At its heart, any percussive hit can be defined by its envelope. A dedicated tool just makes that process more fluid.

The Anatomy of a Kick

Let’s break the kick down into its core components. Understanding these parts is the key to both designing your own sounds and knowing what to look for in a sample.

1. The Transient

The transient is the very beginning of the kick, the initial strike. It’s often under 20 milliseconds long (sometimes up to ~50 ms), but it defines the entire hit’s character and how it cuts through a mix.

With a tool like Kick 3, you can create a transient by drawing a sharp, exponential curve right at the start of the pitch envelope. You could sweep from 20 kHz down to 20 Hz if that aggressive, clicky tone fits your aesthetic.

However, I like to design the kick in context, with the hi-hat and clap already in mind. A kick rarely plays alone; in modern, non-linear drum patterns, hits often overlap. Lately, I’ve been dampening the kick’s high-frequency transient, letting other percussive elements share that space. By limiting its top end from the start, you allow your other hits to work with the kick rather than against it, avoiding the need for surgical EQ later.

2. The Body

The body is what most people call punch. It’s the part of the sound that gives impact. The “feel” of the kick when it’s heard on its own.

This section is shaped by the pitch envelope’s downward sweep toward the final sub note. The steeper the curve, the more aggressive the punch feels. While you can sculpt this in isolation, it’s often better to work against a simple chord drone or bassline. The body has tonal character, and shaping it in context ensures it harmonizes with your track.

While the tail ultimately defines the kick’s “note,” the sweep of the body carries its own musical identity. It’s part of what gives a track its emotional contour. Subtle but essential.

3. The Tail

Finally, the tail, the end of the kick’s journey. This is where the pitch envelope settles into a sustained sub-frequency. The tail’s length is one of the most important choices you’ll make for your low end.

A long tail means the kick is your sub-bass. Be mindful of this; it’s not just a mixing decision but a compositional one. That tail determines how and if a bassline can coexist.

A short tail, on the other hand, turns the kick into a percussive point, a clean impact that leaves space for movement in the low end, room for rhythm and tone to speak.

The right length depends entirely on the groove you’re building.

Pro Tip

You can use your project’s tempo and note length to calculate milliseconds precisely. If you want to be clinical or remove guesswork altogether derive your transient, body, and tail lengths from those values. It’s a great way to keep your kick design rhythmically and musically grounded.

Careful, though, that mindset, while useful, can also drain life from a sound if taken too far. Predictability isn’t always bad, but dull and vapid are. Precision should serve the beat, not replace it.

Conclusion

From the initial, mix-aware transient through the punch of the body and into the sustained weight of the tail, every part of a kick can be designed with intent.

By understanding this anatomy, you move beyond simply choosing samples and begin designing architecture. You’re not just finding a kick that fits; you’re building the foundation your entire track will stand on.

Next up: We'll explore the most critical relationship in dance music making your newly designed kick and your bassline work together in perfect harmony.